There is a fatal urge in the psyche of mankind that compels us to pull at threads. We see a stray end for which we deem there must exist a source, but as we investigate further, lending motive to our seeking, we strive to unravel the mystery to such an exhaustive point that the only remaining secret is the method by which the whole was strapped together in the first place. In other words, we are left holding a wilted and unsubstantiated mess.

This is the folly of the seeker, that he may at once grasp all the parts but have no synthesizing awareness of their purpose. To think that it is even possible to possess a complete understanding of the things that really matter is quite presumptuous, like having the audacity to call oneself a juggler by virtue of holding the clubs in one’s hands. We have endeavored to strip our objects down to the bare bones, a scrutiny that runs deeper than nakedness. Indeed, there is a skill to the art of seeing, but I assure you that stripping plays no part in it. In fact, a wise and saintly pope once said (referring to the apparent immodesty of pornography) that the problem with pornography is not that it shows too much, but too little of the person. The way to truly see something is not to stare with eyes that incinerate or attempt to steal away all mystery, but, as Richard Wilbur says in one of my favorite poems, with eyes that give due regard.

Have you ever spent a considerable amount of time searching for your sunglasses only to discover that they are sitting atop your head? This highlights the noble truth that we are not meant to seek alone, that our eyes are not meant for solitary glances. Gaudium et Spes says that man is ever a puzzle unto himself, meaning that we can never come to full understanding without the communal gaze of our neighbor. A wholly realized perspective includes not only our own contemplation but also that of those around us. It is the very nature of investigation to require at once both detail and context, and this is seen perhaps most clearly in the telling of detective stories.

What is it that makes a mystery tale so enticing? While it may be satisfying for some to finally reach the ending and discover the secret devices of the culprit, I would venture to suggest that the real excitement lies in the juxtaposition of the ambiguous “who” with the indubitable “what.” The facts become essential but only in the context of the larger storytelling. It’s true enough that face value is not valuable unless it faces you toward the right face. Truth is certainly unchangeable but context is the spotlight that illuminates that truth.

The prolific author, dame of detective stories, and queen of sass, Dorothy Sayers, made her name by composing mysteries that were simply drenched in wit. Her celebrated characters, Harriet Vane and Lord Peter Wimsey, have enchanted readers with their fierce banter and unrelenting attention to both detail and context as they dance between the thresholds of absurdity and cleverness. They teach us about the advantages of the well- chosen word

and the practiced skills of perception, but at the same time they are often forced to be content with their own limitations and uncertainties.

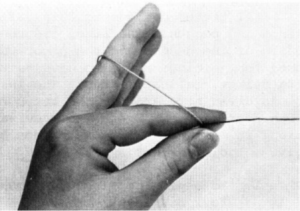

We do a disservice to the modern mind by refusing to cherish the mystery of the unknown. Studies have shown that the very act of online “googling” has had significant negative impacts on our ability to retain information. Why are we so unable to sit quietly in the clandestine rendezvous of thought? The great Romantic poet, John Keats, spoke of the genius, especially present in the works of Shakespeare, of what he referred to as “negative capability, that is, when man is capable of being in uncertainties” and is willing to contemplate the world without having to make sense of all its mysteries. Sometimes we seem to put so much stock in the novelty of thread counts that we destroy their very charm with the tediousness of counting.

Authentic wit is quickly becoming an endangered species in the taxonomy of speech. We have wit-tled down our standards to allow the ends of the spectrum to pollute our correspondence. On the one end we have sarcasm, wit’s tactless backhand, which literally in its Greek root means “tearing of the flesh”. At the other end we have irony, wit’s annoying younger sibling, which relies on either ignorance or opposites to make a point. Now don’t get me wrong, I flirt with the edges of the spectrum myself, but to maintain the healthy balance between the two is where the real innovation of the witling lies. Like a level that must maintain the bubble between the lines, we must only strike the hammer of our wit when the forces are properly aligned. And what is the supreme art of wit? What is it that makes a remark so refreshingly shrewd? It is the ability to find the common thread, a task that requires again both attention to detail and a vivid awareness of the larger stage at play.

Wit consists first in identifying a thread and at once having the grace to leave it raveled.

Wherever there is an absolute triumph in literature you will certainly find a sharp wit behind the crafting of its language. Think of Shakespeare’s endlessly layered dialogue, the common sense of Chesterton’s humor, Austen’s tongue in cheek depictions of propriety, Wilde’s seamless turning of phrase, and the delightful absurdities of a Wodehouse character.

Just like a synapse, wit requires twists, and turns, and tangles so as to minimize the leaping distance our consciousness must travel. For no matter how close the boundaries of wit may hover, a leap there indeed must be in order to fully amalgamate the venture! If science teaches us anything it is th at there is always more to discover. If this is true, then every experience should be one that fosters a sense of wonder; every encounter with another person should evoke a stirring of awe; every footstep should yield a possibility. Wit is the compilation of the learned experiences of a person that is then smoothed in delightful aromatic strokes over the toast of the present moment. As Alexander Pope once said, wit gives us back the “notion of the mind.”

at there is always more to discover. If this is true, then every experience should be one that fosters a sense of wonder; every encounter with another person should evoke a stirring of awe; every footstep should yield a possibility. Wit is the compilation of the learned experiences of a person that is then smoothed in delightful aromatic strokes over the toast of the present moment. As Alexander Pope once said, wit gives us back the “notion of the mind.”

True wit is nature to advantage dressed,

What oft was thought, but ne’er so well expressed,

Something, whose truth convinced at sight we find,

That gives us back the notion of the mind.

-Alexander Pope, “An Essay On Criticism”

So, I suppose this is my blithe attempt to resuscitate the modern mind with the whimsical airs of wit. While the disheveling of modern conversation does not wholly disgruntle me, I must confess that I am, to steal the phrase from Wodehouse, far from gruntled. It is my sincere hope that we may one day learn to clothe ourselves in the faint itchiness of wonder’s sweater while ridding ourselves of the compulsion to pull at every stray thread; that we may lower our vehicular ceilings and allow our hair to become tangled in the fresh freedoms of a moving perspective; that we may, in time, come to sit comfortably in the uncertainties of a negative capability. If perspicuity is the fruit of a leavened mind then wit is undoubtedly the yeast that makes it rise.

“Do you find it easy to get drunk on words?”

“So easy that, to tell you the truth, I am seldom perfectly sober.”

-Dorothy Sayers, Gaudy Night