Disclaimer: This may be the strangest post I have ever written. I can only excuse myself by reiterating the complexity of the woman’s brain, full of tireless, synaptic tangles that are able to thread together any two topics, no matter how trivial. Men, read no further if you are squeamish. Or maybe, that’s precisely why you should read. Whatever your decision, I consider myself fully disclaimed

It’s not the least bit unusual to imagine one’s soul as truly hailing from bygone decades, nor is it even a little uncanny for this nostalgia to revolve around the vintage charm of the 1920s. I have many reasons for favoring this particular era of history: a love of jazz, an affinity for hats, a strange desire to chain myself to a bridge for the women’s suffrage movement. Others might ask, “Why, Steph, would you not want to travel back to the time of Jesus, or Dante, or when togas were fashionable?” I certainly have a deep love of the past and a wanderlust that extends throughout all the realms of time, yet I cannot imagine myself living any earlier than the Roaring Twenties. The reason may be attributed to a simple (yet striking) female intuition about this decade, namely that the twenties welcomed the advent of the sanitary napkin.

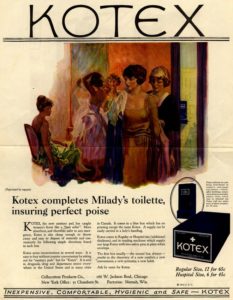

There’s a lot you can learn from the history of Kotex.

I know this may seem an uncomfortable topic. Nearly a hundred years after the invention of Kotex we still find it difficult to discuss this very natural, womanly need. Yet, alas, we do not as a society always shy from everything that is uncomfortable. There are poop emoji icons everywhere: on pillows, on lamps, on coffee cups. We love to perseverate on this disgusting bodily function because a pile of poop is nothing but a conglomeration of waste materials that, once expelled, give our bodies reason to rejoice. But menstruation is a different matter, a bloody mess (so to speak); it’s a feminine wound, the loss of potential motherhood, the shedding of one’s own body. This thought makes people cringe, so we tend to waltz around the subject with a blindfold, swathing it with an array of graceful and discreet language and pretending that Aunt Flo is a real person who comes to cause mischief each month.

Yes, we put a face on poop, but I have yet to see a personified tampon emoji in my iphone. If ever there is a time when words are completely unnecessary, it’s in the midst of the menses.

Me: What do you mean you can’t hang out?!!!

Friend: “Tampon emoji”

Me: Say no more, girl.

However, I digress. The point is that there is something magical about feminine products. Isn’t that a nice thing to call them? Feminine products? The phrase sounds so innocent and blasé but it has been crafted from years of relentless propriety. In fact, the first ad for Kotex in the publication Good Housekeeping, described the napkins as a way to “insure poise in the daintiest frocks,” and they were later described in the Ladies Home Journal as being “in the wardrobe of Her Royal Daintiness.” Semantics always matter.

Women have a long history of fighting to be seen and accepted, so it only seems fitting that this special Kotex material was originally designed as a product of war.

During World War I, the shortage of cotton prompted the invention of a cotton alternative, Cellucotton, trademarked by the Kimberly-Clark Corporation to be used as a sterile bandage for wounded soldiers. Made from wood pulp, Cellucotton was found to be five times more absorbent than cotton. The clever and resourceful nurses soon found a better use for it.

[Rather interesting side note: while my writing has often been full of periods it has never been so frankly about them; so I thank you for bearing with me through this entire cycle thus far.]

And here, at last, is the apogee I have been so awkwardly climbing to: Kotex, like the hearts of all women, is designed to be receptive.

Is this an episode of Stranger Things? Have we just entered the upside down? Are we really having this conversation? Well, my friends, this is I, an insufferable woman who could probably reflect at length on the ontology of a raisin; yet today I have chosen to muse on the womanly properties of Cellucotton. Thank you for being here.

I grew up reading the Redwall Series, a collection of books that center around an imaginary abbey in Mossflower Wood, tended and cared for by a hodgepodge of woodland creatures that fight battles, and wear habits, and believe in the promises of unyielding hope. In the series, the Abbot carefully chooses a name for each season (The Summer of the Lazy Trout, The Summer of the Late Rose, etc) and the Nameday is marked by a great celebration. Maybe it is some sort of lingering and endearing memory of this tradition that motivates me, but I have resorted, as of late, to a similar tradition of my own. Each year, beginning with my birthday (and the start of my “personal” new year), is now christened with a certain theme, the most recent being named: “The Year of Receptivity.”

habits, and believe in the promises of unyielding hope. In the series, the Abbot carefully chooses a name for each season (The Summer of the Lazy Trout, The Summer of the Late Rose, etc) and the Nameday is marked by a great celebration. Maybe it is some sort of lingering and endearing memory of this tradition that motivates me, but I have resorted, as of late, to a similar tradition of my own. Each year, beginning with my birthday (and the start of my “personal” new year), is now christened with a certain theme, the most recent being named: “The Year of Receptivity.”

Though I suppose it could equally have been dubbed: “The Year of the Absorbent Kotex.”

Receptivity has been a virtue hotly debated, perhaps because it falls into that mélange of characteristics we might attribute to the “fairer sex.” Extreme feminists who want to be equal to men in both dignity and nature may advocate for shirking this quality. At the other end of the spectrum, independent women who champion the complementarity of man and woman may confess, with woeful desperation, to being guilty of its poor practice. Some regard a woman’s receptivity as a weakness (“frailty thy name is woman”) and others see it as strength (“let us be elegant or die!”), the latter cohort believing this to be one of the only remaining human qualities that can save the world.

In my reflections during this past year, I have spent a great deal of time purging the wily thickets of receptivity. I’ve learned through trial and error, through intuition and tireless investigation, that receptivity is not a passive surrender, but an active invitation to let others settle in one’s presence. It means recognizing that, as Aristotle said, we are knit in the very fabrics of our beings to be social; and this requires intentional time set aside to give others the due regard they are owed. It means becoming as absorbent and hospitable as Cellucotten, that miraculous product so attentive to immediate needs. For, like the Virgin Mary, we are also called to ponder in our hearts and absorb the truth as it suddenly (or even subtly) strikes.

I once went on pilgrimage to Medjugorje, a dusty town in Bosnia-Herzegovina, and met a man in a box. The box was a tiny confessional and the man was a Korean priest who spoke very little English. He could not articulate well in my particular linguistic variety so he resorted to a flourishing demonstration with a Kleenex box. The box bounced before me as he wildly gesticulated, and I gleaned from his performance the following conversation:

“Imagine,” he said, “Our Lady is this box.”

“Ok, Father.”

“You are the Kleenex.”

“…..I’m not sure I follow.”

“You must be at home in the womb of Our Lady.”

“I need to be a Kleenex in Our Lady’s womb?”

“Yes, like Jesus. You must seek a home in her womb.”

And it was there in that box, while meditating on another box (also containing that precious and miraculous product know as Cellucotten), that I felt a shift in the gravitational pull of my subjectivity, or what Hildebrand calls Eigenleben. I realized that receptivity is a gift, a power, a light. This is what it means to be a strong woman. Women’s souls are meant to “be fashioned as a shelter in which others souls may unfold.” (Edith Stein)

To be a container that is filled, not by force, but by beckon, where others are able to discover their own worth, this is the true exercise of receptivity! This is the power that is 5x more absorbent than petty compliments and small talk. This is authentic affirmation. We should declare it more often to one another. Come; dwell here in my heart. Come; let’s discover who we are together. No one does this better than women.

It’s true that sometimes, after endless digging, the only discovery we make is that our magical time of the month has arrived, the red badge of courage that marks the maturity of woman. In Germany they call it “Strawberry Week.” In South Africa they may say that “Granny’s stuck in traffic.” But it’s the French, as always, who sum it up best:

“The English have landed.”

Yes, the 1920s saw the advent of the sanitary napkin. Women who were once ashamed of their own bodies, hiding away in embarrassment for weeks out of the year, were now emboldened to step out and walk fully in their receptivity without fear. In modern times, some women continue to fight a daily battle for respect and equality. They fear this greater exposure has come with a price. That’s a blog post for another time. It will suffice for now to reflect on the great triumph of those World War I nurses, who seized the opportunity to be savvy, and forever changed the way women would interact with society.

Now if someone could just get me a tampon emoji, I’ll be on my way.

only you could put these things together in the most graceful, WITTY, encouraging way! <3 love you