ONCE UPON A TIME

I almost drowned once, that is, until a towering man wearing river shoes came to save me.

Well, who’s to say what would have happened had he not been there? I mean, I’m an average swimmer. But as I clung to that rock, with the rapids sweeping my hair backwards into a glorious crown of matted clumps, I certainly had my doubts and felt an imminent need to channel my inner Pocahontas. Only instead of raising my voice in song, I was gurgling incoherently and trying not to be offended that my bosom friend, the river, was literally slapping me in the face. I had far less poise than a Disney princess but an equal intrigue as to the question of what was around “the bend.” (For some strange reason my dreams extended just beyond it.)

I was contemplating whether or not I should let go, surrender to the current, and simply “look once more” around this elusive curvature, when suddenly I saw a hand stretched out before me. The hand was attached to a man who was attached to a fashionable pair of river shoes that were, likewise, attached to a nearby slippery rock.

Needless to say, I was instantly attached-well, my heart was attached anyway. My corporal being was far from it, in fact, my body was frenziedly flailing like a non-fish in water. And really at this point in time I would have been excited to see Marcel the Shell with shoes on, as long as his shoes had some decent traction on them.

“Take my hand!” The man yelled with a rippling chest. (It was hard to tell if it was actually his chest rippling or simply a result of the deluge that was assaulting my eyes, but ripples there were nonetheless.)

“I can’t!” I sputtered back with all the attractiveness I could muster. It’s quite difficult to intentionally muster much of anything when you’re fighting for your life. It’s not that I didn’t want to; it’s just that under the circumstances, I was a little preoccupied.

“You have to!”

Now, I consider myself to be a reasonably obedient person, so when a Herculean man orders me to grasp what are presumably the phalanges of salvation, thereby plucking me from the throes of danger, it is almost inevitable that I will comply.

I did.

The man then cradled me in his arms and leapt from slippery rock to slippery rock before placing me down in a rumpled mess of safety. He gazed into my eyes with a look that begged the question, and I exhaled deeply with a sigh that had no comment. What words could I say to thank such a gesture? I wanted them to be gracious yet confident, sexy yet mysterious.

They weren’t.

“My tube,” I whispered to that piercing, handsome countenance, “I lost my tube. I’ll get charged if I don’t return it.”

He went to retrieve the tube. And I went to retrieve my dignity, but it was of no use. It had been swept away and was probably being held hostage downstream by Grandmother Willow.

And so goes the brief tale of my folly in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. Of the many battles that happened in the region, I’m sure that none were quite so embarrassing as this, what I have now dubbed the Battle of the River Bend.

Now, that’s not the end (or even the beginning) of a very true story that happened to me. But if it piqued your interest in even the smallest of ways-if it somehow stirred the inner puddle of your curiosity; if it delightfully opened a new landscape for your subjectivity to explore and frolic about; if you enjoyed the recounting of that particular “time” and the things that happened “once upon” it-then you give testimony to the universal posture of the human heart towards story.

STORYTELLING AND MYTH

We are drawn (by some sort of intrinsic impetus) to adventure, to mystery, to danger, and to triumph. Our hearts long to be enchanted, to be quickened, and to be arrested by wonder. We are fascinated by great stories, and none more, perhaps, than that particular art of storytelling referred to as myth.

The word myth is originally derived from the Greek word, mythos, meaning “word,” or “tale,” or “true narrative.” Yet somewhere along the line, the word myth took on a connotation as being something that is unreal, farcical, imaginary. This idea of myth being at odds with truth was more recently epitomized in the popular show Mythbusters in which certain elements of the scientific method were applied to testing the validity of various rumors, urban legends, and “myths.” While the show was a delightful blend of science and tomfoolery, it was not faithful to the authentic substance of myth, treating it as some kind of idle gossip waiting to be exposed instead of what it truly is: the thread with which awe is woven.

You don’t bust a myth; myths bust you.

The truth is that the ancient origins of myth were steeped in truth. They were used to reveal innate realities, realities more evidently observed when contrasted with the seeming “un-realities” of a well-told fantasy story. Tolkien speaks of this element of fantasy as being a method by which man becomes a sub-creator, making a “Secondary World” that the mind can enter into and encounter truth. The story maker relates what is “true” according to the laws of that world. Tolkien goes on to say:

“The keener and the clearer is the reason, the better fantasy will it make. If men were ever in a state in which they did not want to know or could not perceive truth (facts or evidence), then Fantasy would languish until they were cured. If they ever get into that state (it would not seem at all possible), Fantasy will perish and become Morbid Delusion.” [1]

It would seem, at least according to Tolkien, that fantasy is the building block of myth, and he considered it to be the highest and most potent form of art. And how he would scoff at some of the modern day fairy stories! It’s true that we are attracted to myth; however, we do not always know how to recognize it, define it, or detect its inauthentic portrayal. This is how life-sucking (no pun intended) stories such as Twilight and Fifty Shades of Grey have been slyly allowed to pollute our sacred, modern bookshelves, like desperate inanities that can only find their meaning in the plague of rampant sensationalism.

ENTER MY PLEA

We should, indeed we must, resurrect a desire for authentic myth in our culture! Too long have we suffered under the rise of vapid and meaningless stories, stories whose raisons d’etre are nothing more than to stir the irreverent, primitive appetites of man or to dangle an impossibly elusive string before the unthinking shallows of the conscious mind. We have let our sense of fantasy deteriorate into, as Tolkien noted, “morbid delusion.”

We must not settle for delusions, and if we must, especially not the morbid kind.

And so, just as Cartoon Pocahontas shouldered the mission to teach John Smith the beauty, and truth, and value of her landscape, so do I hereby accept the task to champion the resurrection of authentic myth in these here united states of being.

DEFINING MYTH

This is undoubtedly a germane moment to define our terms a little bit, but unfortunately this may prove to be a difficult task. You see, the subject of myth and the elements that compose it have been hotly debated among scholars for centuries. Even some of the greatest myth-makers of all time seemed to grapple with the definition.

“By the bye, we now need a new word for the ‘science of the nature of myths’ since ‘mythology’ has been appropriated to the myths themselves. Would ‘mythonomy’ do? I am quite serious. If your views are not a complete error this subject will become more important and it’s worth while trying to get a good word before they invent a beastly one.” (C. S. Lewis to J.R.R. Tolkien, in Lewis 1988: 255)

While the answer to the question of myth’s taxonomy is simply beyond the scope of this very humble blog, we can still endeavor to make a few modest remarks.

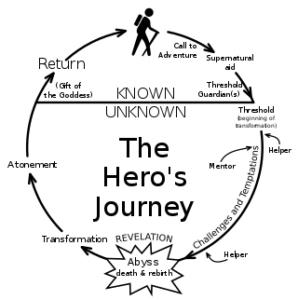

Joseph Campbell is perhaps one of the most well known authors to comment on the  subject of comparative mythology. In his book, “The Hero with a Thousand Faces,” he discusses his theory regarding the homogeneous narrative arc that seemed to be fundamental to all hero stories. What he originally dubbed the “monomyth” is now more commonly referred to as the “Hero’s Journey.” He summarizes his basic theory in the introduction:

subject of comparative mythology. In his book, “The Hero with a Thousand Faces,” he discusses his theory regarding the homogeneous narrative arc that seemed to be fundamental to all hero stories. What he originally dubbed the “monomyth” is now more commonly referred to as the “Hero’s Journey.” He summarizes his basic theory in the introduction:

“A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.” [2]

I don’t know about you, but there’s nothing like a good boon bestowed by a fellow man. While Campbell’s monomyth originally consisted of seventeen stages, it has since been condensed into twelve by Hollywood screenwriter, Christopher Vogler. They are as follows:

- Ordinary World

- Call to Adventure

- Refusal

- Meeting with the Mentor

- Crossing the Threshold

- Tests, Allies, Enemies

- Approach to the Innermost Cave

- Ordeal

- Reward (seizing the sword)

- The Road Back

- Resurrection

- Return with Elixir

There is a particular familiarity to these stages, and understandably so, as this framework lays the blueprint for every story that has ever been considered epic or moving or memorable. In fact, Campbell’s work has been explicitly credited with inspiring many marvels of cinema including Star Wars, Indiana Jones, and The Lion King. That’s quite a rap sheet. I mean, goodness, The Lion King was such a staple of my childhood that I’m not even sure what my life would look like without it! Come on, I know I’m not the only one who was profoundly impacted by the death of Mufasa. #spoileralert

Continuing our exploration of the characteristics of myth, we can turn now to the very special quality of “bizarreness” that is often present in these stories. John McDowell, a professor at the University of  Pittsburgh, suggests that myths must be essentially “counter-factual in featuring actors and actions that confound the conventions of routine experience.” [3] Tolkien also describes Fantasy as having a particular advantage, that of “arresting strangeness.” What does this mean? It means that myths are often immersed in a certain kind of weirdness, or, in other words, mythical stories contain some sort of stark contrast to what we would expect to encounter in every day life. They are inherently unexpected. They are shocking. And in being shocked, we are successfully smoked from our interior rabbit holes to face the world in a fresh and exciting way.

Pittsburgh, suggests that myths must be essentially “counter-factual in featuring actors and actions that confound the conventions of routine experience.” [3] Tolkien also describes Fantasy as having a particular advantage, that of “arresting strangeness.” What does this mean? It means that myths are often immersed in a certain kind of weirdness, or, in other words, mythical stories contain some sort of stark contrast to what we would expect to encounter in every day life. They are inherently unexpected. They are shocking. And in being shocked, we are successfully smoked from our interior rabbit holes to face the world in a fresh and exciting way.

G.K. Chesterton is not as well known for his mythical writings; however, he had a keen understanding of the importance of looking at reality through a peculiar yet revitalizing lens. In his great masterpiece, The Everlasting Man, he describes his views on myth:

“In a word, mythology is a search; it is something that combines a recurrent desire with a recurrent doubt, mixing a most hungry sincerity in the idea of seeking for a place with a most dark and deep and mysterious levity about all the places found.” [4]

Marilyn Chandler McEntyre tells us that the power of stories lies in their ability to mirror a community back to itself, and that these stories can provide both refuge and challenges that become instruments of healing. I realize that asking to resurrect authentic myth is kind of a tall order, especially since we find it so difficult to define. But maybe the point is simply that we can never fully understand myth, because the ultimate goal of mythical stories is to invoke a sense of wonder and enchantment while at the same time rousing conviction both for the discovery of truth and the prioritization of desire.

Perhaps it is better if we avoid the smokescreen of definitions and move on to the reasons why myths are important. Though I regrettably will be unable to illustrate my point by painting with all the colors of the wind, I can; however, conclude by giving a few suggestions of:

WHY AUTHENTIC MYTH SHOULD AND MUST BE PRESERVED

-

Myths are healthy for the brain.

We as humans are hard wired for stories. The fields of social science and psychology have given us fascinating revelations as to the effect of storytelling on the human brain. For instance, it makes sense that while listening to another person tell a story we “hear” the words and interpret what they mean, but the brain takes it one step further. Not only do we receive and analyze the raw material of language, but also, as we listen to a story, we simultaneously stimulate the part of the brain that would be used to “experience” the events of the story! This is why stories stick with us. They become a part of our own experience. Not to mention the fact that story listening releases a number of “feel good” hormones (dopamine and oxytocin) that help to deepen our connections with others. There is a reason why the most persuasive people are great bards.

-

Stories are the fabric of our lives.

When I was fortunate enough to spend a very brief stint of time at Oxford, my creative writing tutor said something so wonderful that it has deeply resonated with me ever since. Speaking on the subject of writer’s block, she told us that this idea is in fact a myth (referring, of course, to the currently regarded definition of myth, and not to the sense of authentic myth being discussed in this blog). “You and your life are full of stories,” she said. “And you have the capacity to tell them. You matter.”

Our lives unfold before us like the pages of a book. Each day has a beginning, a middle, and an end; each moment is besieged by tragedy or joy, desperation or delight; and each encounter with another person is a  new story read and a new story made. Marilyn Chandler McEntyre describes how our internal loci are shaped by the stories with which we feed ourselves:

new story read and a new story made. Marilyn Chandler McEntyre describes how our internal loci are shaped by the stories with which we feed ourselves:

“We derive our basic expectations from the narrative patterns we internalize-the hope of a happy ending, the recognition of the need for sacrifice, a sense of how communities work, an understanding of family. Stories provide the basic plotlines and in the infinite variations on those plots help us to negotiate the open middle ground between predictability and surprise.” [5]

There is a theory first circulated by George Polti in the 19th century that there are only thirty-six plots or “dramatic situations” that exist. It is certainly true that there are repetitious patterns in stories, but that does not necessarily make them monotonous. If anything, it brings hope and delight to the daily predictabilities. Tolkien again:

“Spring is, of course, not really less beautiful because we have seen or heard of other like events: like events, never from world’s beginning to world’s end the same event. Each leaf, of oak and ash and thorn, is a unique embodiment of the pattern, and for some this very year may be the embodiment, the first ever seen and recognized, though oaks have put forth leave for countless generations of men.” [1]

Myths have the power to instruct, enchant, heal, grow, soften, and inspire. Their imagery and language are the threads of the human tapestry-and vibrant fabrics require vibrant stories.

-

Humans long for the Transcendentals

Humans want to understand things. Our rationality is what separates us biologically from so many other organisms. We yearn for meaning. Who am I? Why did this happen? What do I do? Where should I go? When will I know? These questions turn inside of us like a restless wheel, and in the demanding of their answers we are, in actuality, begging to be told a story.

Tolkien (have I mentioned him yet?) ceaselessly touted the virtues of fantasy literature and thought that these stories were especially suited for helping us give vent to these squirrelly emotions. For him, all fairy stories contained three main purposes: Recovery, Escape, and Consolation. [1]

- Recovery includes the “regaining of a clear view.” It enables us to see things as we were meant to see them, apart from our own biases and subjectivities. In doing this we have a “renewal of health.” Fairy stories help us to become more humble by showing us the way reality should truly be seen.

- Escape is a word that Tolkien felt he had to defend. During his time, “escapist” type of literature was very popular and he bemoaned the critics’ “misuse of language” when referring to the term. He held firmly that the particular kind of “escape” afforded by fairy stories was not a “running away” but rather, a “freeing of the prisoner.” For him, the type of escape yielded by fairy stories was both practical and heroic.

- Consolation was the last, and perhaps most important, of the fairy story virtues-the happy ending. This is where Tolkien’s description of “fairy stories” will differ from some of the more classic definitions of myth, for what might be considered a “classic myth” very often ends in tragedy. While Tolkien would consider tragedy or “dyscatastrophe” reserved for works of drama, he also acknowledged that sorrow is often necessary for the joy of deliverance. This joy he refers to as “eucatastrophe,” the highest function of fairy tale. He goes on to posit that the Christian Story is the eucatastrophe of Man’s history, the greatest story ever told. Tying this back to the subject of myth, C.S. Lewis would echo this statement by suggesting that the story of Jesus is the True Myth, or in other words, in Jesus “myth became fact.”

“For this is the marriage of heaven and earth: Perfect Myth and Perfect Fact, claiming not only our love and our obedience, but also our wonder and delight, addressed to the savage, the child, and the poet in each one of us no less than to the moralist, the scholar, and the philosopher” [6]

It would seem that in the crafting and reading of myth that we are trying, in some fashion, to satisfy our longing for truth, beauty, and goodness. Joseph Pearce, in his essay titled, “Tolkien and Lewis: Masters of Myth, Tellers of Truth,” comments on the sense of transcendence at the heart of all mythical stories:

“It is the inescapable and unavoidable presence of God that makes myth such a powerful conveyor of reality. If the essential ingredients of reality, of life, are not physical but metaphysical, it follows that true stories must reflect these metaphysical realities. If goodness, truth, beauty and love are at the heart of all that is truly real, and if these things transcend the three dimensions and the five senses, it follows that stories must convey this essential transcendence in order to be real and true. Any story that fails to convey this mystical transcendence and remains solely within a world of three dimensions and five senses will not only be lacking in reality, it will be dead. Lifeless.” [7]

Even the great theologian, Thomas Aquinas, felt impelled to describe the intimate relationship between philosophy and myth: “Because philosophy arises from awe, a philosopher is bound in his way to be a lover of myths and poetic fables. Poets and philosophers are alike in being big with wonder.” [8]

These are only a few of the very many reasons why myths are important. Relatively speaking this “mythonomy” (as Lewis called it) is still a new and exciting field. There is much to learn from this very prescient art and we can only look with optimistic expressions toward myth’s future milieu.

WHERE WE ARE NOW (A CONCLUSION OF SORTS)

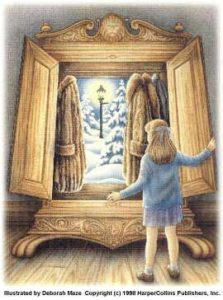

It’s true that I lament the apparent lack of present day stories of myth. But I also know that we don’t always get it wrong. For who hasn’t shouldered the burden of the ring with Frodo Baggins, or swooned before Aragorn’s rugged virtue, or longed to retire in the rolling hills of the Shire? And who hasn’t searched the back wall of their closet for the door to Narnia, or wondered what it would be like to ride on the back of a benevolent lion, or imagined having tea with a centaur?

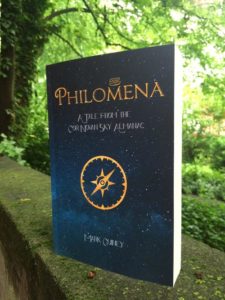

These are stories that technically belong to the modern era and there is hope yet still. I recently read a book that is restoring my hope for the future of myth-telling. Mark Guiney’s delightful work, “Philomena: A Tale from the Cor Novan Sky Almanac,” couldn’t be more apt to the conversation. A coming of age story set in  the land of Cor Nova, this tale is imaginative and thrilling from beginning to end. While written primarily for a young adult audience, Guiney has still managed to construct a plot threaded with subtle truth bombs that speak to all the levels and maturities of the human experience. From flying airships to secret languages, the story is fueled by adventure and grounded by moral questions of loyalty, power, mission, and justice. And more than that, it satisfies all the criteria for the Hero’s Journey and Tolkien’s virtues of Restoration, Escape, and Consolation. It restores my confidence that there are still, indeed, good stories to tell.

the land of Cor Nova, this tale is imaginative and thrilling from beginning to end. While written primarily for a young adult audience, Guiney has still managed to construct a plot threaded with subtle truth bombs that speak to all the levels and maturities of the human experience. From flying airships to secret languages, the story is fueled by adventure and grounded by moral questions of loyalty, power, mission, and justice. And more than that, it satisfies all the criteria for the Hero’s Journey and Tolkien’s virtues of Restoration, Escape, and Consolation. It restores my confidence that there are still, indeed, good stories to tell.

But even as we expand our search to farther realms, well beyond the classic definitions and nuanced intricacies of what we might (now) consider “authentic myth,” it is perhaps of greater importance to acknowledge the more looming pertinence of a very special kind of story: that of our own. It is absolutely vital that we tell each other our stories, ruminate on them, discover the locales of their interplay, and learn from them. Maya Angelou famously said, “ There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside you.” And I think she was right.

There is nothing more liberating, more potent, or more real than the fierce encounter when two human stories collide and become joint adventure.

I first met Mark in the pouring rain outside an unsuspecting, West Virginia coffee shop, just down the road from Harpers Ferry. My hair was probably matted into the same disheveled clump, yet I didn’t hesitate this time to take the hand that was extended to me. I learned my lesson the first time, at the river’s edge. And what does the future hold? Well, my friends, that is something that only myth will tell.

You can check out Mark’s book here: https://www.skyalmanac.com/

References:

- Tolkien, J.R.R. On Fairy-Stories. “Essays Presented to Charles Williams.” Oxford University Press, 1947.

- Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. New World Library; Third edition, 2008.

- McDowell, John. “What is Myth.” Folklore Forum, vol. 29 (2), 1998.

- Chesterton, G.K. The Everlasting Man. Oxford City Press, 2011

- McEntyre, Marilyn Chandler. Caring for Words in a Culture of Lies. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2009.

- Lewis, C.S. God in the Dock. “Myth became Fact.” Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1972.

- Pearce, Joseph. Beauteous Truth. “Tolkien and Lewis: Masters of Myth, Tellers of Truth.” St Augustine’s Press, 2014.

- Aquinas, Thomas. Commentary on Aristotle’s Metaphysics, chapter 1, lecture 3, commentary